This time’s sort-of-historical blog post is another bisexual I never met – fashion designer Ossie Clark. He’s also my second Elegantly Dressed Wednesday subject, because not only could he look pretty smart himself, he made lots of rich and lucky women look good, and had an influence on the style of plenty of poorer women too – including the teenage me.

Born in 1942 and murdered in 1996, Ossie Clark was a terrific designer who made some of his best clothes in the late 60s and early 70s.

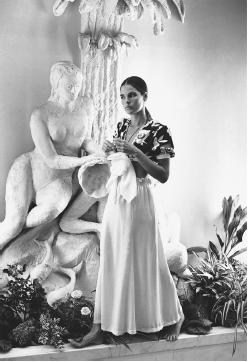

The clothes he made tended to the flowing, like the pictures I’ve posted here.

A kind of 40s meets 70s crepe or chiffon. And very sexy, in my opinion.

I can’t find many pictures that will allow me to post them here, but the site for the London Victoria and Albert Museum’s 2003-04 exhibition has quite a few to look at.

A fashion historian said to me that she thought he really liked women, because his clothes made female bodies look good. They didn’t require you to have a particular body shape – certainly not the rake-thin type usually associated with fashion.

Of course, nowadays his clothes are characterised as “vintage” so you can buy them in auction houses and upmarket clothing emporia. Unsurprisingly, they are really expensive – this one (below) was sold in 2004 for £3592.

Still, it’s the sort of thing I’d love to wear if I had the money/ thought that spending that sort of money on clothes was morally defensible!

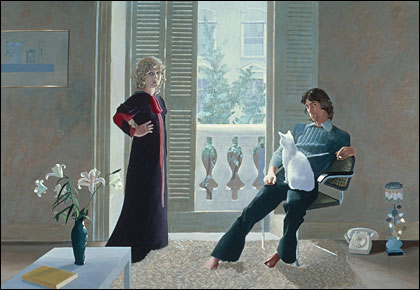

Many of the clothes he designed were done in collaboration with his fabric designer wife, Celia Birtwell, who nowadays has a rather pretty collection for Top Shop. There are some more of their 70s clothes on that site too.

This really famous picture of them was painted by David Hockney and now hangs in Tate Britain, in London.

So what about his bi-ness? He’s written about on this blog, entitled Gay for Today, but I think the writer is a wee bit snide by saying:

In 1969 he married Celia Birtwell. Although Ossie was openly bisexual and carried on many affairs with men, he and Birtwell had two sons together.

And your point is, Mr Gay for Today?

What can I easily find out about him? Well, he lived the Swinging Sixties life, with the sex, drugs and rock and roll that that implied – particularly the drug part, which apparently set his marriage and career, and subsequently his whole life, on the skids.

In 1996 he was murdered by his (male) ex-lover, very violently indeed. A sad and sorry end really to such a creative life.

For more on him, go here, and his posthumously published diaries are available here. I feel there’s a lot more I could write, but - boo-hoo – no time for the research.

He’s also been in the news recently, as his sons tried to stop his name being used as a new Ossie Clark brand, which they considered exploitation.

Speaking of fashion designers, I have a feeling that Calvin Klein was bi too. Can anyone advise?